Planning for execution

What’s broken and why

Established in the 1960s, the way we plan and execute construction projects hasn’t fundamentally changed, with one exception: the individuals creating and managing the plan.

In the past, planning and scheduling were often handled by Superintendents who had a deep understanding of the project. However, as the tools used to create and manage plans have become increasingly complex, the need for specialists to use the software has also increased.

Today, professional schedulers with limited construction experience, no stake in the outcome, and who do not speak “construction” are managing and dictating plans to the field.

The reliance on professional schedulers has become a crutch. For example, when the field realizes that work will be delayed, it becomes the scheduler’s problem to solve. The field has somehow been relieved of the duty of working expeditiously. We’ve become more willing to accept delays because the scheduling “magic” will find more time.

But the scheduler cannot create more time; nobody can. Instead, the scheduler has become a master at hiding extra time (float) and a novice at making a schedule that reflects the real world and how the project will be built. Why?

The introduction of “modern” CPM software in the late 1990s made it all too easy to create schedules with thousands, even tens of thousands, of activities, making the scheduler appear adept. When distributed as a Gantt chart, they quickly turn into 100-page task lists that are outdated before they’re read. Even executives struggle to review them. Here’s the dead giveaway that the project director can’t read your schedule: they focus solely on the end date.

We’re left with inexperienced “professionals” with no skin in the game who create long, outdated, and complex plans that don’t represent reality, which leads to the consumer (the field) neglecting it altogether, which reinforces the lack of need for a plan that isn’t useless.

The cycle then becomes: The schedule doesn’t provide value, so it doesn’t matter, so don’t put in too much effort to deliver value.

This has led to schedules that are disconnected from reality, that are for “checking a box,” and that do little for those who need it the most: the field.

Objection 1: Schedulers should not work for the builder

There are beliefs in the industry that the person managing the plan should be agnostic to the builder or developer. While incentives are mostly aligned—build it while maximizing safety, speed, and quality while minimizing cost and risk—if a builder can’t leverage their planning & execution skills to be more competitive and/or profitable, why even have General Contractors?

Objection 2: We’ve been building for years, no fire here.

Projects are taking longer to finish; this has been a steady trend since the 1960s (when CPM was introduced to construction). Yes, this considers design inflation (CAD has the same effect on design as CPM does on planning). Longer durations mean more costs (direct, indirect, and opportunity) for the same project for all stakeholders.

Principles & Practices

I firmly believe if we adopt some planning principles that focus on execution, and how we execute, then we can improve the success rate of projects.

If we break down the three primary purposes of construction scheduling, they are:

- Creating the plan

- Communicating the plan

- Executing (updating) the plan

The scheduling tools we have today are mediocre at #1 and fail miserably at #2 and #3. It’s beyond the scope of this essay to dive into specifics, but you can glean from the rest of my posts what my strong opinions are.

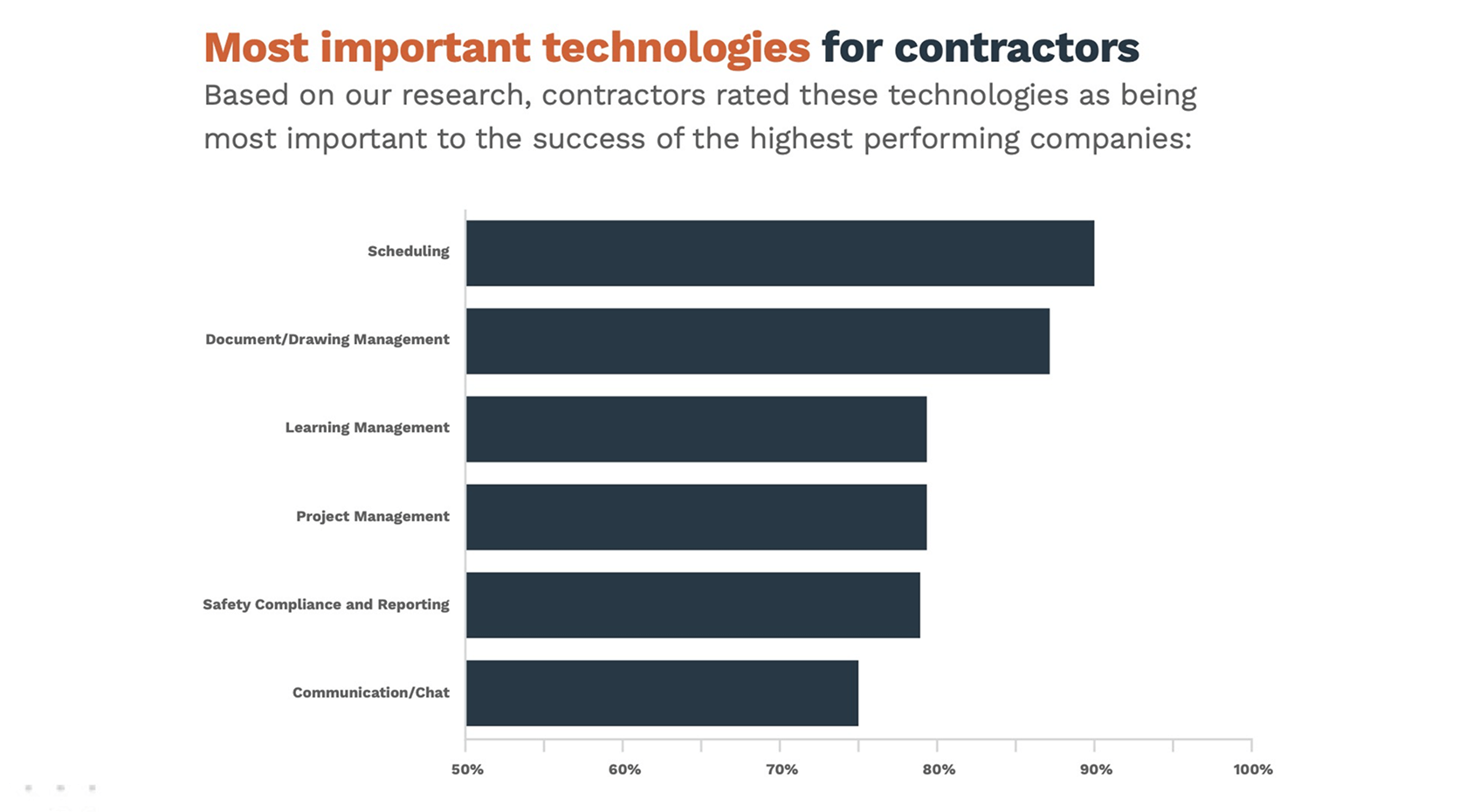

The field has opinions too. It doesn’t take much research to conclude that contractors aren’t happy with the status quo on schedule.

Principles

Focus on the field

Superintendents, foremen, laborers, and anyone who works in the field need as much support as possible. Everyone else, Project Managers, Estimators, Schedulers, etc., is responsible for supporting the field with everything it needs to get the job done.

Understand Priorities

If we could work on one thing today, what would it be? That question is not asked enough. There is always an answer.

The Gantt chart doesn’t have it. You can show Total Float, but there are arguments against sharing it. One is that it tells subcontractors exactly how late they can be without getting back-charged.

I’m only aware of one tool that shares priority without giving away Total Float. Planflow considers many factors, including total float, remaining project duration, and historical trade performance, when calculating priority.

Give them the “why”

Last week, the owner of a drywall company shared a project schedule created by the general contractor with me. His question was, “The schedule says I start hanging walls on April 1st; can I start earlier?”

The answer is I don’t know. The GC decided not to show activity relationships on the 60-page Gantt chart. In their defense, they never are, as they would take the whole row, and there wouldn’t be room for anything else.

The schedule is not the end all.

The superintendent is beholden to the schedule and safety and quality and cashflow, etc. The schedule drives decisions around these, but can also take a back seat to them. If done properly, the schedule is rooted in logic and common sense.

Issues come up; collaboration is key to resolving them

We must stop relying on a meeting with a scheduler once a month to identify roadblocks, hoping the scheduler correctly documents and links the issue. Anyone on the job needs to identify constraints that can or are blocking them as they arise. It can’t wait until the next meeting.

The plan is how you execute the schedule

And safety, and quality, and profit, etc. The plan needs to incorporate all the needs and constraints of a project for it to be viable.

Here is a good analogy between construction projects and hiking: The schedule is like a map with a route you intend to take from A to B. The plan is what you see in the real world from where you are now. Many projects only look down at their maps while walking, which will still get you to where you’re going, but you may trip on some branches, step in some puddles, or trek through some thick brush. It’s better just to use the schedule to find your next marker and then put the map away and walk, only stopping at the marker or when you need to re-orientate.

It takes an army

Construction is not a single-player sport; it requires the effort of hundreds or even thousands of contributors, whether on or off the battlefield.

In the Army, I was told that if you aren’t an infantryman, then your job is to support the infantry. The same is true in construction: if you’re not physically installing material, your job is to support the people who are.

If workers are standing around doing nothing, it’s not their fault; it is the fault of the people who are supposed to be helping them and getting out of their way.